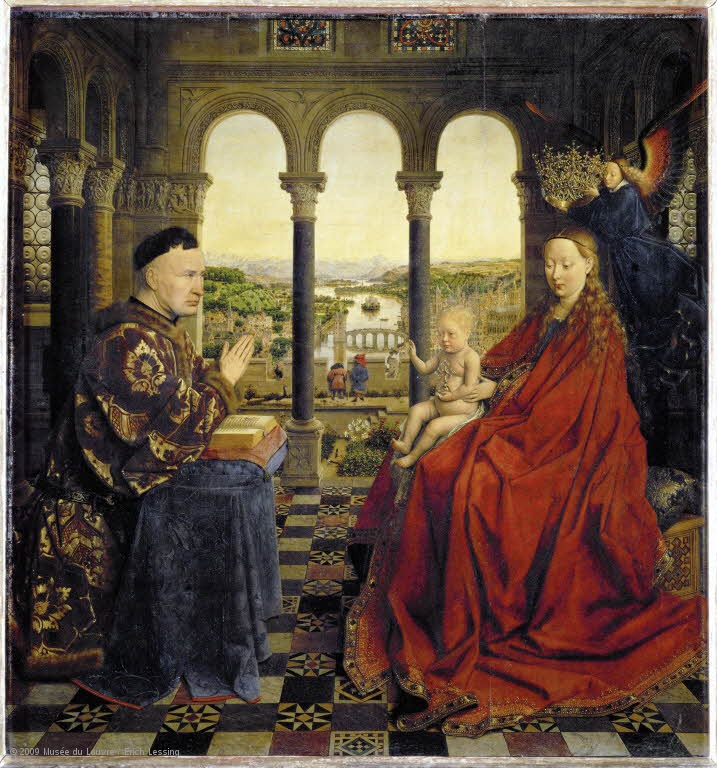

The Virgin and Child with Chancellor Rolin

Jan Van Eyck is often credited as the inventor of oil painting, and although he is certainly the first artist who fully mastered the technique, oils had earlier been used in Indian and Chinese paintings of the fifth century.

Nevertheless, he is known as its father, and the many who have admired his extraordinary Arnolfini Marriage at the National Gallery will appreciate that he truly was a visionary.

The small painting is not only sublimely beautiful, it is so rich with puzzling detail, religious iconography and metaphor, it has transfixed artists since it was completed.

Van Eyck even signed the painting unconventionally, as an inscription on the wall above the convex mirror in the background, ‘Jan Van Eyck was here 1434’.

There is no certainty about the date of birth of the Flemish artist, which is estimated at between 1390-1395. Almost nothing definitive has been recorded about his early life. He became court painter to Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, in 1425, and was paid a yearly stipend – unusual at the time, when artists relied on earning money from commissions. His salary was exceptionally high when he started, and repeatedly doubled as his value to the Duke grew.

In addition to his painting tasks, he acted as a personal ambassador for his master, trying to secure him a suitable bride, travelling to the Iberian Peninsula to sound out Princess Isabella of Spain, and more successfully on his next journey to kindle the interest of Princess Isabella of Portugal.

While working for the Duke, he was also asked by the royal chancellor Nicholas Rolin to provide a grand painting to decorate his own chapel. Despite his modest family background, Rolin’s reputation as a lawyer led to his advancement to this high office.

Obviously, he wished to make his great standing as a court dignitary abundantly clear, and it resulted in one of the most blatant vanity projects of all time. He required Van Eyck to create a portrait of himself with the Virgin and Child.

Dressed in much finery, brocade and mink furs, Rolin is seen ostentatiously kneeling before a velvet-covered prayer desk, as the infant Jesus blesses him, holding a small globe as a symbol of Christ’s power over creation. Mary is seated on a throne holding the young child, while angels carry an imposing jewelled crown to her head.

The composition opens up through a triple archway with Roman columns, to reveal a bucolic landscape, and formal garden with a basilica. The three protagonists in the picture create a sculptural presence, with the picture enabling the artist to demonstrate his skill at composition, and use of perspective, inspired by the room’s architecture and ornamental tiling.

Here, Van Eyck utilises symbolism to represent scenes from the Old and New Testaments, and Christ’s transition between the two, with reliefs depicting the Seven Deadly Sins seen above Rolin’s head.

Besides betraying a desire for self-aggrandisement that would have given Citizen Kane pause, Rolin was an enlightened patron to a number of artists. Importantly, he supported Rogier Van der Weyden in creating his outstanding Polyptich of the Last Judgement.

Along with Robert Campin, Van Eyck was the leading representative of this new style of painting in oils, soon to become widespread as artists discovered that it allowed light and detail to be captured with greater brilliance.

He was able to take on other commissions with the Duke’s agreement, foremost of which is the magnificent Ghent Altarpiece. It has had a turbulent history, surviving riots and revolutions, including being more recently looted by the Nazis. It was discovered after the war hidden in a salt mine alongside other stolen treasures, and was painstakingly restored.

This work has undergone much scrutiny over the years, because the inscription on it reads ‘Hubert van Eyck major quonemo reportus’ – greater than anyone.

This was Jan’s brother, who reportedly started the work, with Jan finishing it and signing ‘arte secundus’ – second best in art. However, experts maintain these signatures where a fiction invented by Ghent humanists in the 16th century, and that Hubert was responsible only for its sculptural framework.

Made up of twelve vast wooden panels that open to reveal exquisitely painted biblical depictions, it is one of the highest pinnacles of Christian art.

Commentators have also debated endlessly about which of the three Van Eyck’s is the most perfect example of his powers – The Arnolfini Portrait with its intricate detail and the mystical power of its symbolism, the breathtaking majesty of the Ghent Altarpiece, or the electrifying Virgin and Child with Chancellor Rodin.

It seems of little consequence which of these masterpieces is the finer, and Britain is fortunate to have The Arnolfini Portrait on display in the capital, a permanent beacon for many art lovers, alongside his delightful Portrait of a Man from 1434.

Van Eyck achieved his precise finish by painting layer after layer of thin veils of oil, which also allowed for his manipulation of perspective and indirect lighting.

He clearly used a very fine brush, and experts agree that on occasion he worked with a single hair. His attention to detail, and the devotion he gave garments, flooring, implements, fruit, even wooden surfaces, was revolutionary, and inspired much of the art produced in future years.

Even in the 19th century Van Eyck’s works remained the standard benchmark against which all painting that followed was to be judged.

It is probably the case that without his influence, the work of early giants like Piero della Francesca, Andrea Mantegna, and Sandro Botticelli may have been diminished, as well as the highest achievements of the masters of the High Renaissance, Raphael and da Vinci.